Every six months, each “Facilities-based Provider of Broadband Connections to End Users” in the U.S. is required to report to the FCC on the number and speed of its fixed broadband connections (cable, DSL, fiber or satellite) in each U.S. Census block.

This data, collected through the FCC’s semiannual Form 477 reporting process, gives the agency a unique trove of information on the state of home broadband access at the very local level. It puts the FCC in a position to provide each American community with a fairly accurate map of its own local digital divide — the Census tracts where most households have broadband Internet service vs. the tracts where many or most households don’t.

And from 2010 to 2014, that’s just what the FCC did. Twice a year the agency published a Form-477-based “Internet Access Service Report“. The report was accompanied by data files ranking every U.S. Census tract on a scale of 1 to 5, indicating the ratio of total reported home broadband connections to total households. Each number in the scale represented a household connection range of 20%, with a 5 indicating a broadband-connection-to-household ratio of 80% or more, a 4 indicating 60% to 79%, etc. A ranking of 1 meant that the residential broadband connections reported by provider added up to fewer than 20% of the tract’s households.

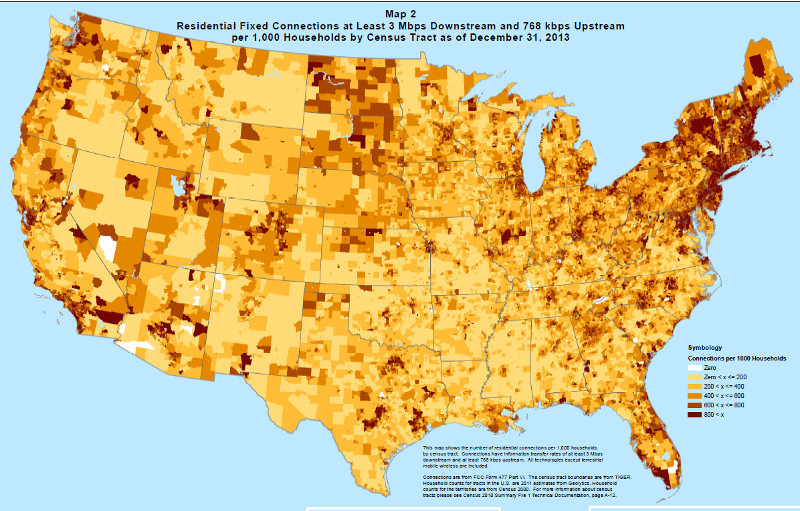

Here’s one of the FCC’s own national maps attached to the December 2014 report (based on December 2013 data).

And here’s a map of the same data for the city of Cleveland, created by local NDIA affiliate Connect Your Community.

Form 477 tract data is pretty much the only resource available to local leaders and advocates trying to understand the geography of broadband exclusion in our own communities. The U.S. Census American Community Survey now provides community-wide information on household Internet access for “places” with populations above 60,000 — e.g. for whole cities — but it will be at least three more years before the ACS starts breaking those numbers down to the tract level. So for now, the ACS may tell us that a third of a city’s households don’t have Internet access, but can’t tell us which of the city’s neighborhoods are worst connected. And ACS household Internet data is completely unavailable for smaller municipalities, not to mention unincorporated rural communities.

But Form 477 data can help local advocates, planners and policymakers fill all these gaps… or could, until the FCC mysteriously stopped publishing it.

The last Internet Access Service Report posted on the the FCC website dates from October 2014, fifteen months ago. It includes data from the second half of 2013. Since then, two reporting cycles have come and gone, with no updated reports or data releases.

Providers were required to submit the same information to the FCC for the first half of 2014 as in previous years. The reporting requirements were tweaked for the second half of the year (July through December), but the submission deadline didn’t change. As 2016 begins, the FCC has yet to share household subscription from either 2014 reporting period with the public.

We’d love to know when the reports will again be available.. There’s no indication on the agency’s website that its Internet Access Service Reports, or publication of the Form 477 tract-level data, have been formally discontinued. But there’s also no notice as to when the long-overdue 2014 data might be released.

Is this only a problem for a few research geeks? Not at all. As more local communities take the initiative to deal with broadband access and adoption questions for our own residents, the importance of good localized data — and the difficulty of finding it — becomes ever more evident.

In recent months, for example, Form 477 data allowed a coalition of public and community organizations in Cleveland, Milwaukee, Dayton and other cities to demonstrate a clear link between broadband exclusion and neighborhood poverty in comments submitted to FCC in the Charter-Time Warner merger case. Form 477 data was also used by a research group affiliated with MetroHealth, the county hospital in Cleveland, to document the relationship between neighborhood broadband adoption ratios and patient adoption and use of the hospital’s personal health record application – helping build the case for collaboration between the hospital and local digital inclusion programs.

The FCC’s neighborhood-level household broadband data matters. It’s a unique, valuable resource for community leaders and digital inclusion practitioners and advocates.

The FCC should act now to get its public release of this data back on schedule.