This guest blog post was written by Jessamyn West, a librarian and rural technology educator in Randolph Vermont. Jessamyn also works for the Internet Archive’s Open Library project. Through NDIA’s listserve, Jessamyn discovered Roberto Gallardo and his Tedx Talk. Roberto is an Associate Extension Professor of the Mississippi State University Extension and runs the Intelligent Community Institute.

I’ve been a rural technology educator in Central Vermont for fifteen years. It’s easy when you’re doing one-on-one instruction–helping people fill out government forms, learning to text, or signing up for an email account–to believe that your problems are unique and local. I was struck by Roberto Gallardo’s TEDx Jackson (MS) presentation on The Rural Digital Divide about just how similar some of our concerns are, despite the geographic and cultural disparity of our users.

Most importantly, Roberto was talking about programs that work.

The good news is that the digital economy means that more people have more opportunity to work from where they are. The digital economy is where the growth is.

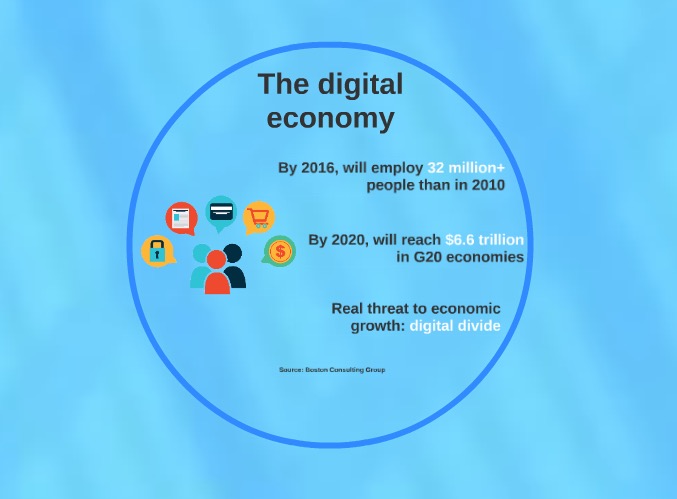

As someone who has both a local and a “gig economy” job, I appreciate being able to use my technology skills to work for a Bay Area employer to help balance the low local wages with the very high quality of life in rural Vermont. However, the digital divide concerns are real. Broadband that used to be fast in 2010 barely qualifies as broadband today. And this broadband gap disproportionately affects rural communities.

Conventional wisdom tells us that the wireline broadband gap isn’t a concern since so many people can access broadband via mobile devices, but as Roberto points out, the same people who have issues affording broadband in the first place are also going to be hamstrung by limited data plans. Mobile-only access is not the way to create a thriving digital economy.

I was amused while watching this part because my broadband is significantly slower than 25/3. I am the web person for the Vermont Library Association and recently had to upload a 7GB video to YouTube. My smart idea was to go to the library and use their connection which was theoretically 100Mb but when I got there I found their upload speeds were less than 1Mb and no one there actually knew why. This is a cultural issue as much as a technical one where the people providing the service–and I have a wonderful terrific library–are not the ones using it. I wound up uploading the video at home and it took nearly a day during which the rest of my internet slowed to a crawl.

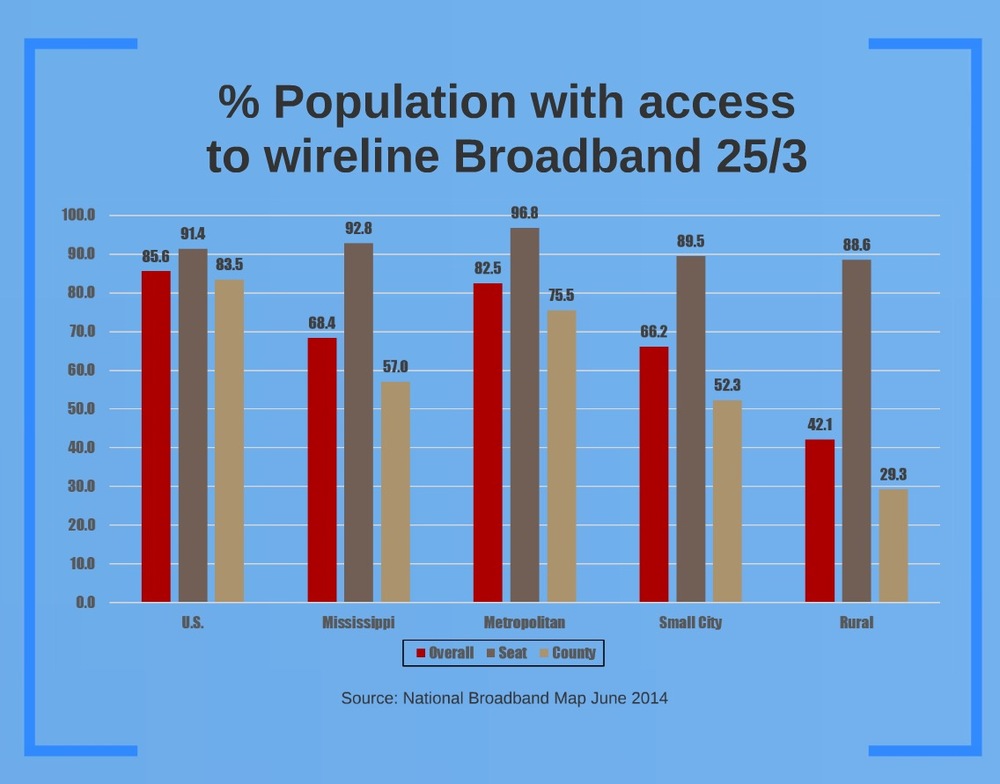

Roberto discusses how the Mississippi State University Extension program is perfectly set up to do information dissemination thanks to the fact that they were set up to do this for agricultural purposes when they were founded. Their agents are trusted by the rural communities they serve so that when they have a message like “This is going to disrupt you, let’s help you catch up” they are speaking to an attentive audience.

Starting with awareness, moving towards asset-based community development and then moving on to implementation of specific community based programs, this approach to bridging the digital divide incorporates the community fully from start to finish. And it works.

Roberto reminds us that the digital divide is not just about the ability to get access to broadband, though that is part of it, it’s also about having the ability or even interest, to use it when you get it. The programs from the Mississippi State University Extension meet the public where they are and help share a world that they may have only heard about on television or the newspaper.